Black Child, White Family: How One Mother is Healing from the Impact of Her Transracial Adoption

A young Thenedra Roots couldn’t wait to show her mother the hogs.

She was living with a family who owned a farm, and Roots wanted to gross her mother out during the visit by having her watch the sickly pigs get hauled off.

“I remember being really excited to show my mom the process of taking away the pigs that were sick and dead,” Roots said. “I really wanted to be silly and goofy with her.”

Then, something changed for 11-year-old Roots when her mother sat down to do her hair.

As the preteen complained of pain while her mom combed her thick hair, Roots’ white adoptive mother snickered. Her biological mother turned to the woman and said sharply, “You just wait until she gets her period, then she’ll really be complaining about it hurts.”

This memory is vivid for Roots, who is now 31 and a mother of four. When she heard those words, she realized her situation may be more permanent than she thought.

It was also the last time she saw her biological mother.

Roots and her three brothers were placed in the foster care system in her home state of Minnesota after their mother struggled with drug addiction, alcoholism and mental health issues.

When Roots was 11, she was officially adopted by her new family. She stayed with her youngest brother while the others went to live with relatives.

Though she and her brother had newfound stability, clothes and food, they were Black children adopted into a white family unprepared for raising traumatized children.

Adoption isn’t a choice yet adoptees are constantly pressured to be grateful.

Roots always seemed to be an outsider in the white spaces of her upbringing in the small town of Vernon Center, Minn. She internalized negative views about her features as a result of racism she faced within and outside the walls of her home.

Though her experiences shaped her as a Black woman and mother who is raising four Black children, the road was tough.

November is National Adoption Month, and it’s not a time of celebration for her. Instead, Roots, a licensed alcohol and drug counselor who works as a mental health non-profit leader, uses this time as an opportunity to raise awareness about a system that can leave many children traumatized.

Effects of Transracial Adoption on Black Children

It was a challenge for Roots to accept her hair and her curvy body growing up a Black adoptee in a white home. Her features were constantly the center of hurtful jokes from both her family and peers.

Roots admitted that she at times even joined in.

For a child who had already suffered traumatic experiences, it was her way of protecting herself.

“(I started) internalizing comments and jokes that were being made and also being the person who made the jokes in order to somehow shield myself from the hurt,” she said. “I just didn’t want people to know that the things that people said were hurtful to me and so I just went along with it. You start to contemplate your value as a person, like who you are, especially as a girl, especially as a prepubescent girl in those really critical times of development.”

Black children are disproportionately represented in the foster care system. While they make up just 14 percent of the American population, these children account for 23 percent of the foster care population.

White women make up most of the mothers to adoptive children entering kindergarten at 77 percent.

In 1972, the National Association of Black Social Workers released its position statement on transracial adoption, urging the system to place Black children with Black families. Yet transracial adoptions increase each year in the United States.

But are white families equipped to enrich Black children in their own culture? This certainly wasn’t the case for Roots and her brother.

I didn’t have girlfriends, I didn’t have a mentor, I didn’t have a doctor, I didn’t have a community

Thenedra Roots

“There’s a lot of cultural implications that come with adopting a child whose identities are outside of your race — just the basic hair and skin care that we didn’t get, not connecting us with someone who could do our hair, ” said Roots, who earnestly discussed her adoption story in further detail on the Minnesota-based podcast Terrible, Thanks for Asking.

In 2017, 73 percent of non-white adoptees were placed with white families.

“It causes a lot of harm and can be very detrimental to the adoptee’s mental health and wellness,” said Roots, who recently cut ties with her own adoptive parents due to truths she shared on the podcast. “I think that anyone who is considering adopting needs to be asked the question of ‘why.’ What is your purpose of adopting a child outside of your race and ethnicity?

“If the answer is ‘because I love all children,’ then that’s a red flag.”

How Adoption Shapes Motherhood

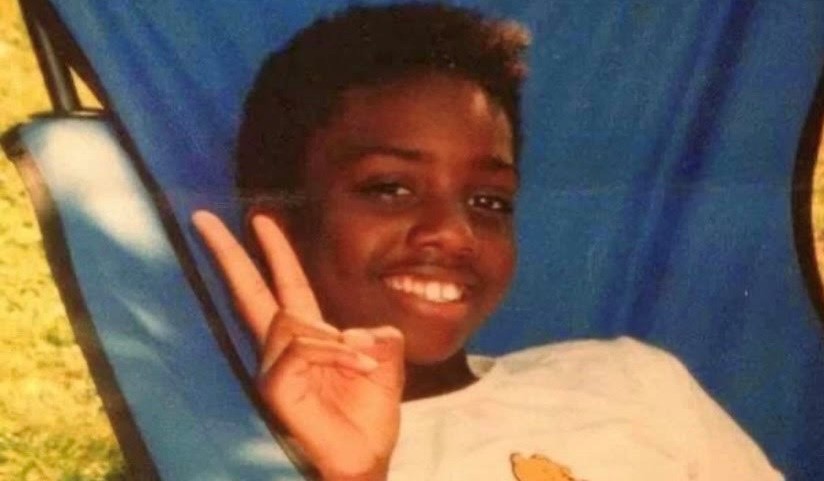

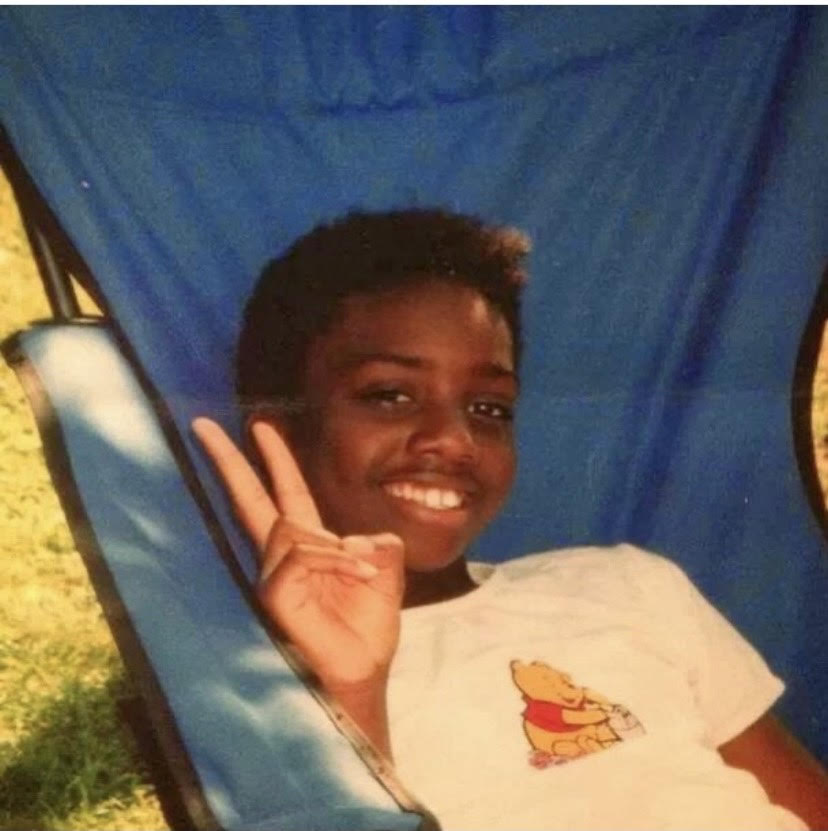

Roots doesn’t have a picture of herself before the age of 11, so she’s serious about collecting family photos.

She has four young boys, including twins, from three months old to 3-years-old. She uses her Instagram page to showcase photos of her family and to advocate for adoptees.

She said she’s made many connections on social media with others who share her story.

As a child of adoption, her experiences — especially with racism — have influenced her parenting.

Her family lives in the Bloomington, Minn., which is more than 75 percent white and just nine percent Black. Roots must manufacture Black spaces and experiences — including time with their uncle who lives nearby — to ensure her children see themselves in the world.

She also wants to make sure they can rely on her, all the way.

“As much as it’s very hard to reason with the trantruming 3-and-a-half-year-old, I don’t want to shut them down,” Roots said. “I want them to feel safe showing me every emotion, even ones that drain me, so that they know I love them when they’re happy and that I love them pissed off.”

Roots didn’t have that as a child. She stepped up to care for her brothers when she was with her biological mother and sadly never found a sense of belonging among her adoptive family.

She’s sure to celebrate the Blackness of her children because it was something she was denied. Providing them that is part of her healing.

This is why National Adoption Month is more reflective than celebratory for Roots, whose identity was swiftly erased when she was removed from her home and placed with a white family in a white town.

“I didn’t have girlfriends, I didn’t have a mentor, I didn’t have a doctor, I didn’t have a community, I didn’t have a dentist, a teacher — none of that,” Roots said. “It’s healing for me to also be a voice to support other adoptees who have had similar experiences and have never felt safe or comfortable sharing the not-so-pretty side of it. It is vulnerable.

“This month for me is just about healing. It’s not about celebrating. It’s about healing and connecting with other people.”